Research and Fact Based- Special Mention

/Porous Pockets of Guwahati – Striving for Memorable Cities

Witnessing the transformational journey that my hometown– Guwahati, has undergone in the last two decades, it is as if I have grown up with a childhood friend whose history I have been curious about and a future that I am in anticipation of. My inquisitiveness about my city and the urban experiences of the generations before me led to the discovery of a YouTube video; a song sequence from the Assamese movie Manab Aru Danab (1970), titled “Moi Kun?” (Who Am I?), that unfolds a fascinatingly different image of the city that young people like me would be unfamiliar with. While present-day Guwahati is a densely packed urban space with high-rises and private vehicles, the music-video provides a glimpse into the dwindling Assam-type houses, public transportation, lush green covers, and open public spaces that are faintly present in small pockets within the city.

Known as the “Gateway to the North East,” Guwahati is now the fastest-growing city and largest metropolis within India’s North-East Region [NER], emerging as a hub for commerce, communication, education, and healthcare. Although the city landscape and its economy continue to grow post-Liberalization, the population within the metropolitan region has stabilized since 2001 due to economic and geopolitical developments. While several reports indicate that Assam’s population has risen to 3.5 crores in 2021, there is a decline in fertility rates and improvement in life expectancy, which has increased the population of older people (60 years and above). It has been predicted that this age group will grow three-fold from 19 lakh in 2011 to 53 lakh in 2036, making them 13% of the state’s total population. Evolving with the presence of a prominent elderly demographic, I began wondering how Guwahati has transformed from the nostalgic evocations of the residents from the heart of the town.

In a quest to learn more, I came across W.W. Hunter's (1897) account of revenue collection which noted the “Gauhati Municipal Board’s” jurisdiction of 2.95 square miles in 1892 by and large comprising of Panbazar, Paltanbazar, Uzanbazar, and Fancybazar. While the city expanded radially, my family stayed put in Uzanbazar for almost six generations! This triggered an opportunity for me to reach out to older people from these places and understand how they were coping with their hometown changing. Although these notable localities are not without transformation, they hold what many nostalgically refer to as “the old-world charm” which seeps into the present, giving them a “porous” character. Through the course of these interviews, I realized how it is not only the city that changes but simultaneously its people and their ways of perceiving their environment. The change that has occurred is not only in terms of "seeing" (visual infrastructure) but also more profound in terms of “feeling” (perceptual experiences). What emerged were narratives related to the natural environment, commuting, public spaces, and community.

Metamorphic Infrastructure & Urban Ecology

Discussing their presence in the city, Mr. Tapan Dutta Chaudhuri (69 years old) narrates how his family had moved from the countryside to Dighalipukhuri, Uzanbazar around the 1930s during his father’s boyhood. Mr. Chaudhuri became reminiscent of the archetypal Assam-type infrastructure that has now metamorphosed into high-rise RCC buildings. An amalgamation of the Assamese way of living and modern British intervention, this form of architecture was developed by colonial engineers who extensively studied this region’s topography in the aftermath of the devastating 1897 Earthquake to create sustainable infrastructure. With the rising density of people and pressure on land resources, these dwellings have gradually become obsolete in favor of commercial, rent-based constructions [Fig.1&2]. A steady rise in housing and land prices has resulted in widening class distinctions that has edged out the lower-income groups to the periphery and the gentrification of central urban areas, which only the old elite population has managed to survive.

Figs. 1 and 2: Metamorphic presence of Assam-type houses with the new RCC high-rises

With the haphazard concretization of spaces, the presence of nature has begun to fade away from the urban. My grandmother, Mrs. Santana Chowdhury (82 years old), wistfully recalls the sounds of birds and crickets chirping around dusk. She even states that her children growing up were fascinated by junaki poruwa (Fireflies) in their backyard, but unfortunately, they have become a rare sight. Light and noise pollution within the city has also triggered the disappearance of birds such as the ghonsirika (House-Sparrow) and many other insects. While sounds of construction and traffic now dominate the city’s aural landscapes, people associate pockets of green spaces near the riverfront and ponds in the old neighborhoods [Fig.3] with tranquility that evokes a sense of closeness to nature.

Fig.3: Sights of nature in old Guwahati

These evocative memories of the natural environment have led to residents nostalgically recalling Guwahati’s past as being more habitable for all life forms in the context of a disappointing present. Mrs. Chowdhury says that the city now feels like coarse concrete that has “swallowed the softness of agricultural lands” that she had witnessed in abundance during the late-1950s when she moved to Uzanbazar after her marriage. Now, much of the city’s flash floods arise due to traditional waterbodies such as wetlands being buried by landfills and settlements. A tributary of Brahmaputra, the Bharalu running across the city annually chokes during the monsoon. People are no longer able to fish or bathe here as it has turned highly toxic over the years. This has also led to diminishing aquatic life, negatively impacting the urban ecology.

This disappointment with the urban environment is also triggered by the tactile discomfort associated with heat, dust, grime, sweat, and stickiness due to the changing climatic conditions that have rendered the summers unbearable. A recurring complaint in the conversations was that Guwahati’s weather used to be pleasant, but it isn’t anymore. Such sensorial memories cannot be seen in isolation from the sprawling gated communities built by real-estate developers in the nascent parts of the city. While these manicured landscapes recreate the natural environment within closed walls, they remain inaccessible to the larger society. For the sake of the public, green spaces within the old porous localities of Guwahati require protection from the bulldozing tendencies of neoliberal capital.

Hustling around Town

Recalling his family history, Mr. Arup Kumar Das (74 years old) narrates how his grandfather moved to Panbazar in 1891. Now in the same plot stands his two-story RCC dwelling that houses the fifth generation. Mr. Das fondly remembers the glory days of his childhood when the streets used to be their cricket turf and football grounds. Despite the streets lined with “smelly open drains,” exploring the locality and traversing its boundaries used to be a thrilling endeavor because “the town used to have a sense of openness.” Apart from the business establishments, he distinctly remembers that the locality had only seven houses which multiplied drastically after the state administration shifted from Shillong. With the formation of the new neighboring state of Meghalaya in 1972 and the relocation of Assam’s capital to Dispur, population inflow triggered the growth of Guwahati in the late, ‘70s and '80s.

Similarly, Mr. Das's son remembers how he used to run home from school to immediately pedal around the street on his bicycle. While he did not loiter around town as much, he was familiar with the neighborhood's nooks and corners [Fig. 4]. However, Mr. Das’s grandson is less attuned to his immediate environment than the older generations. He is instead used to the clamor of vehicles and isn’t fond of walking around Panbazar. Adults now deem that the streets are not pedestrian-friendly and fear for the safety of the young primarily because of fast-moving vehicles. However, many paradoxically embrace the convenience that the “Uber Economy” has ushered in. Traveling around the city is no more considered an incredible feat, with private cabs arriving at the doorstep booked via smartphone apps. But steadily increasing traffic without a mass rapid transit system has triggered the construction of several flyovers as a band-aid solution, which has subsequently impacted the Air Quality Index and noise pollution levels.

Fig.4: Streets of Panbazar

While many invoke the rhetoric of progress, there is also an underlying hesitance towards change. A sense of fear emerged among the old when asked about the brand new ropeway. Built by the Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority [GMDA] in a joint venture with a Swiss firm, the ropeway over the Brahmaputra connects the North and South banks. Despite the scenic view that the ride offers, the idea of dangling above the river's swift currents makes many feel uneasy. It is also expensive: crossing the river costs Rs. 100 one-way compared to the traditional ferry, which charges Rs. 5-10! The ferry is still a popular mode of transport, and the river has remained an essential route of connection for many. My father, Mr. Atanu Kumar Chowdhury (62 years old), holds fond memories of riding ferries during his boyhood and reiterates that inland water transportation has served as the working class’s cheap and efficient commute to the city from North Guwahati [Fig. 5]. However, he laments that the authorities have neglected the public transportation systems, such as ferries and city buses, which have the potential to solve multiple urban afflictions.

Fig.5: Sourced from my father‟s family album – M.V. Lachit Ferry

Transformation of the Consumer

Mr. Ujawal K. Deb (82 years old), the owner of Panbazar’s old sweet shop – Gauhati Dairy (est. 1928), was found to be in an animated conversation with his lifelong friend, Mr. P.K. Banerjee, whose wine shop – B.N. Dey & Co (est. 1861) was just a two-minute walk away. Their afternoon ritual was to keep the tradition of “adda” alive. This basically indicated a culture of leisurely chit-chat to a passionate exchange of ideas. These local shops bubbling with conversation in the yester years now remain a vestige of nostalgic memories. Nevertheless, the association of Panbazar with the smell of books and freshly baked bread has remained intact for many as it continues to be a hub of bookstores and inexpensive eateries.

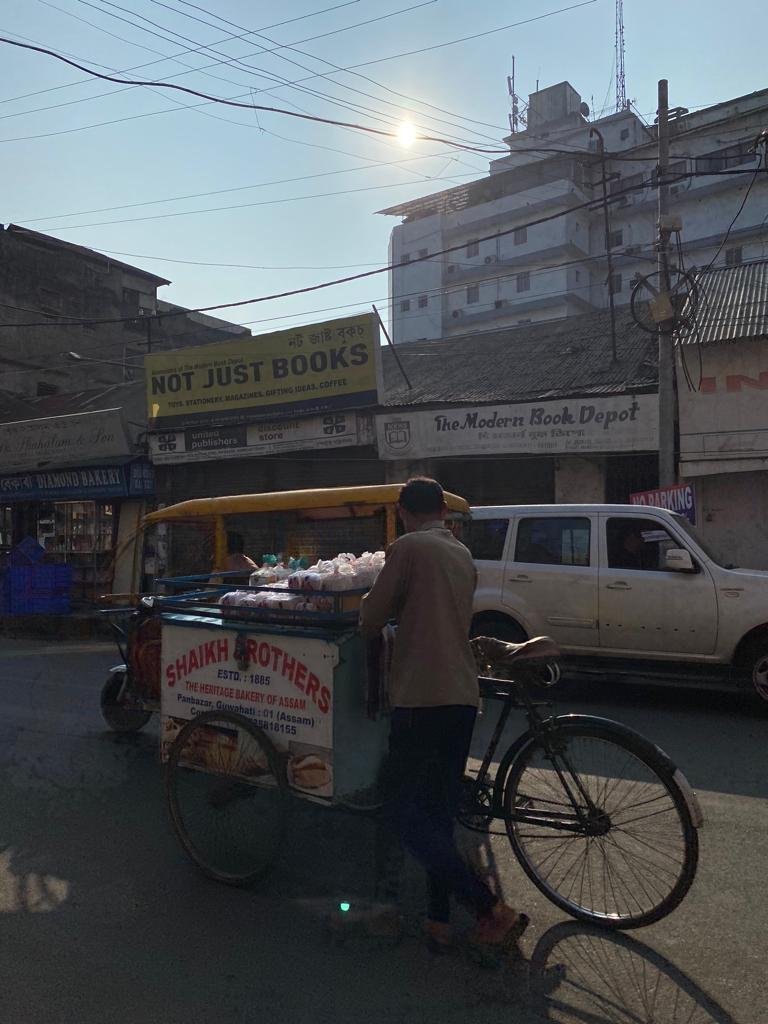

Shaikh Brothers (est. 1885) and Diamond Bakery (est. 1977) carts persist as another symbol of the past [Fig. 6&7]. Among the sea of Swiggy and Zomato delivery personnel, these men cycling around the old neighborhoods hold fond memories for people. Interestingly, they do not purely maintain a detached transactional relationship with their customers. Mr. Shaikh M. Nawaz, the owner of Shaikh Brothers, emphasizes how working around the same routes regularly for years has made their deliverymen familiar to the neighborhood folks. A bond of trust has been nurtured over time in a way that sometimes if they are unable to return the exact change for the money they are paid, it would be adjusted in future transactions. It is now rare to establish such a relationship in the current gig economy, where the consumer remains estranged.

Fig.6&7: Deliverymen with Bakery Carts in Panbazar

Meanwhile, Mrs. Anuradha Borooah (77 years old) wistfully recalls the joy she derived by going around Fancybazar to watch films and shop. Now disabled by a knee injury, she states that she is unable to cope with how intensely city life has transformed. While several malls in the city are comparatively accessible to disabled individuals, Mrs. Borooah feels like these spaces are unfamiliar. On the pyres of single-screen cinemas like Fancybazar’s Kelvin now lies multi-level car parking plazas. The elders certainly miss the charm of the “old talkies”, where entertainment was more or less accessible to all. In contrast, the youth in Guwahati visit malls and cafes where they get to have an otherworldly experience curated through the “ambiance” of the place.

While the elders did complain about the young losing touch with their culture, Mrs. Chowdhury conveyed that she is glad that her granddaughters have more independence than she did to explore and enjoy city life. Although she does not relate to their globalized tastes, she notices an increasing presence of women in public and appreciates how society is gradually becoming “open-minded.” This throws light on how the past is remembered in multiplicities, especially when viewed from varied intersections such as gender, class, or caste. While the past translated to enmeshed and robust community life for some, for others, it also meant greater constraints on their freedom. Although globalization has ushered in diverse choices for the public, many of these multicultural spaces remain exclusionary as they mainly cater to the privileged consumer.

Tenacious Ties: Fields & Festivals

When asked about their concerns regarding Guwahati’s future, the elders mentioned the lack of open spaces. Going down memory lane, Mr. Chaudhuri recalls playing football at Judges Field every morning with boys from his locality [Fig. 8]. Ranging from the ages of 9 to 26, they used to call themselves the “Morning Club.” Others also remember spending their leisure time at Church Field and Latasil. According to Mr. Deb, boys from different communities played together back in his days. But the feelings of solidarity with the neighborhood have presently disintegrated due to a growing socio-economic divide. While a portion of the area now remains with the Christ Church (est. 1844), the rest of the Church Field has partly been constructed into a ticketed recreational space called the Nehru Park. On a separate section of this ground stands Food Villa, a food court with international fast-food chains such as Domino’s. While this is an expensive place that remains inaccessible to many, a line of carts outside the park offers all passersby a range of street food at a reasonable price.

Fig.8: (Bottom row, left) Mr. Chaudhuri with the Morning Club

Although utilized differently, the other fields remain intact. Run privately by the Gauhati Town Club, Judges Field is exclusively for sports training and organized matches. Retaining its flexible character, Latasil has remained a historically significant space. This field was created in 1899 to assert the public’s rights when the local Ekata Sabha was denied access to the Judges Field by the European Club. Furthermore, Latasil is considered the birthplace of urban Bihutoli, as the Rongali Bihu celebrations from the rural settings were first recreated on a stage here in 1952. Recollecting their memories of festivities, elders narrated their sensorial experiences of attending Bihu and Durga Puja: people dressed up in colorful traditional attires, celebratory songs and dances, and food stalls lined up around the perimeter of the field. Interestingly, porosity in terms of culture also exists in the Bihutoli – the indigenous folk forms [Fig. 9] continue to be presented along with new-age singers. While there has been a growing cacophony of traffic during festivals in recent times, these localities have retained an unwavering essence.

Fig.9: Rongali Bihu at Latasil – folk dancers performing Bagurumba, the indigenous dance form of the Bodo Tribe

In discussing tenacious traditions, Mr. Chowdhury presented a picture of Durga Puja celebrations. He mentions, “Unlike the Bengali Dhak, the Bor Dhul is played with the Taal by Kamrupi Dhuliyas here” [Fig. 10]. The Visarjan (immersion) of the worshipped deities during Dashami (Dusherra) in the ghats of these old localities is also another tradition that lives on. While festivals are celebrated with fervor, sites such as Latasil also remain politically significant for the community as it has historically been a site of protest. Open spaces like these have now begun to dwindle, with newer parts of the city rarely having spaces for recreation. The dense occupation of land has created pressure on public spaces, which are already meager and poorly distributed. When compared with the rise of neoliberal spaces of consumption, it reveals the story of rising estrangement within the community where only those who are privileged enough are given access to privately owned communal spaces.

Fig.10: Kamrupiya Dhuliya – folk drummers from indigenous ethnicities such as Kaibarta, Rabha, Koch

Endowing Memorable Cities for Children

Through the conversations with senior citizens, I came across the sensorial experiences of their urban way of life, which have shifted over the years. These lived experiences reveal a growing generational gap, instances of loss, weakening community ties, mounting socio-economic disparity, but also emerging visibility of women in public spaces and technological advancements. In the backdrop of such transformation lies globalization that has catapulted intense, unplanned urban growth, shaping the contemporary story of Guwahati as a city in motion.

Looking back in time and dissecting the nostalgic memories has undoubtedly helped me discern certain layers of place memory. Since the past can be remembered through varied perspectives, it is essential to understand that “going back to the old ways” doesn't always mean the same thing for all. Fascinated by the German-Jewish philosopher – Walter Benjamin, I applied the idea of “porosity” to the older localities of Guwahati, as the remnants of the past here continue to live alongside developments of the present time. While change, especially for Indian cities, is inevitable, nurturing and revitalizing the porous pockets like that of Guwahati may prove to be a fruitful effort in memorializing the character of a city. Interestingly, when asked what kind of a city they wanted to endow to their future generations, they all conveyed the idea of a “memorable city” where people across generations can acknowledge their environment’s history while simultaneously being open to newer configurations of urban space.

Therefore, cities around India must strive to be memorable and livable, where the relics of time alongside the current innovations aid residents in remembering their history. This exploration through conversations with senior citizens of Guwahati throws light on the porous character of old neighborhoods that continue to thrive even under the pressures of the standardizing instincts of the neoliberal, global world. Knowledge about such localities should be made more accessible by according recognition to key establishments and by installing neighborhood maps and signage. Streets should also be made to be more pedestrian-friendly to encourage the exploration of such localities. Moreover, protection and development of open public spaces is the need of the hour for a thriving community life in the city. Cities must ultimately be planned in a manner that is sensitive to the neighborhood’s history, culture, and most importantly, its people in order to be memorable.

Written by:

Arundhati Chowdhury

A resident of Guwahati, Arundhati is an Urban Studies postgraduate from School of Global Affairs, Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University Delhi (AUD). Currently preparing for her next step, her interests include poetry, map-making, and collecting postcards.

This piece is part of Nagrika’s Annual Youth Writing Contest. Through the writing contest we encourage youth to think creatively and innovatively about their cities.