AUTO-mobile to NON-Motorised: Coming full circle

/Mobility interventions in india

The first bicycle race between two cities was officially held in 1869 in France where the winner’s average speed was 13 kms per hour. The first organised automobile competition also took place between two cities in France in 1894, not long after the first bicycle race. The winner won with an average speed of 16 kmph. The evolution of cars and bicycles has been closely intertwined through history. Automobiles, however muscled their way on to the city roads and became a vehicle of choice and aspiration. More than a century later when the mass production of cars and bicycles became a possibility, cities are rethinking this choice between automobiles and what now has a name - ‘non-motorised transport’. The current crisis has led us to think about self-mobility of vehicles in a completely new light. In this new paradigm, the self is not a motor.

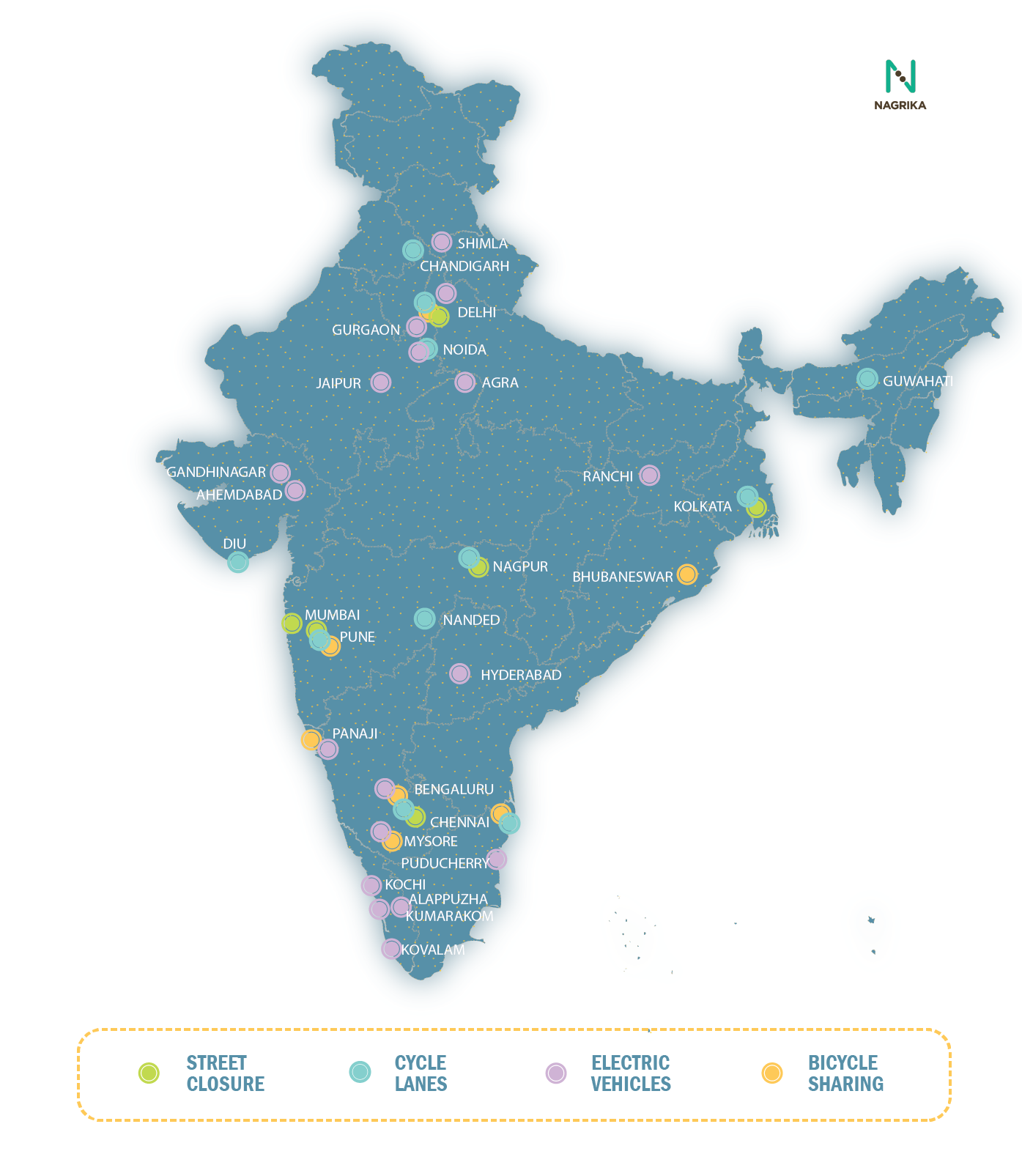

With the needs to maintain social distances, hygiene as well as speed while moving, the entire mobility ecosystem including modes of transport, infrastructure, technology as well as city planning is being revisited. Pedestrian and cycling friendly streets have been a part of mobility discussions for some time now. It is the pandemic, however, which has brought back the need for a mode of transport which is inclusive, accessible and not overburdening on the existing road infrastructure. Turning streets into temporary pedestrian zones and building permanent cycle lanes is emerging as one such response in which countries- including India- are willing to invest. (See the image above)

Pedestrianisation of streets

Temporary reclamation of city streets from motorised vehicles is underway in many cities to expand public spaces for pedestrian mobility, recreation and exercise. Central parts of London, Paris, Vancouver, Philadelphia and New York City shut down motorised vehicles on avenues and main roads to make more open space for socially-distancing public on foot. Open road plan (or slow roads plan) are also being adopted as a means to increase public spaces and allow the movement of cycles and people on the roads, in cities like Milan and Brussels.

Some Indian cities are also giving thrust to similar projects which were already in place. Chennai has already made about 100 kms of pedestrian friendly streets and Chandni Chowk in old Delhi has been fully pedestrianised. Bhopal and Coimbatore are also trying to create more space for pedestrians on their streets through the smart city projects.

Though many of these measures are temporary in nature, they all seek to enhance pedestrian mobility and encourage pedestrianisation of streets.

Cycling Reforms

There has been a boom in the demand for cycles post-lockdown around the world, including India. Cities like Brussels, Bogota, Colombia along with Manila and Rome, which are known for their traffic jams, have added permanent bike lanes to encourage and meet the growing demand for cycling. Cities like Berlin, which already has an extensive cycling network has expanded its cycle lane size while Vancouver, Denver, Budapest, New York, Mexico City have put up temporary cycle lanes by closing off some streets from motorised vehicles.

The India Programme of the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) recently conducted a study which demonstrated 50-65 percent increase in the use of cycles in India. The MoHUA, in response has launched India Cycles4Change challenge for smart cities as a COVID-19 response measure.

Many Indian states and cities have also been involved in this development, with the Kolkata government speeding the process of having cycle bays and Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) deciding to procure 5,000 cycles for Chennai. Private programs and clubs like Noida Cycling Club and the Bicycle Mayor Program have been active in creating awareness campaigns. Jaipur is assessing the feasibility of its roads in terms of space available for cycles. Bengaluru created 34 kms of pop-up bicycle lanes and is also currently crowdsourcing cycling routes in the city. The Noida Cycling Club also suggested a proposal to the government, for pop-up cycle lanes (converting a part of lane reserved for vehicles into a cycle lane) for short-distance trips which could be constructed by re-using parking and service lanes.

NMTs as a way of life

COVID-19 has given an opportunity to revisit the policy priorities regarding mobility in our cities. Recently, Indian Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) recommended pedestrianisation of at least three market places in all million-plus cities and one market place in non-million-plus cities. At the same time, different cities have been taking initiatives to pedestrianise streets or encourage pedestrian and bicycle movement, some of which were discussed above (Also see the image below).

The national policies that encourage non-motorised transport have been in the form of guidance and recommendations provided as part of National Urban Transport Policy, Transit Oriented Development Policy or thrust areas for projects under AMRUT and Smart Cities. The COVID crisis has the ability to change the thinking about NMTs from a ‘project’ lens to a ‘way of life’ in the cities. It already has instilled a demand instead of supply of such solutions. The ‘road’ to transition is still long but a beginning has been made.